As someone working towards financial independence, I regularly review my expenses and look for ways to reduce them without sacrificing my quality of life, especially the recurring ones. Sometimes I switch to a cheaper internet provider during Black Friday, or find ways to lower my electricity bill.

But there’s one expense that takes up a large portion of my monthly budget that I can’t control: my rent. I’m sure I’m not the only one in this situation. A common rule is that you shouldn’t spend more than a third of your salary on rent. I believe this applies to most of you reading this. Unfortunately, for some people, rent can take up half of their salary.

I live in an apartment owned by a company that has more than 3.000 flats in Hamburg. Their business model is simple: instead of building new homes, they buy old flats in popular neighborhoods, renovate them, and raise the rent. Even though there are some rent control rules in Hamburg, there’s not much protection when it comes to rent hikes between tenants after a renovation, even if I’m paying 50% more than the average rent in my neighborhood.

Some might ask why I don’t just move. Well, when you’re trying to rent a place and there’s a long line of people applying, it can take anywhere from three months to even a couple of years to find something that works. Others might suggest moving to a different city, but that’s not an easy choice if you enjoy your life where you are and have friends around you. The only remaining option, then, is to buy a property.

Homeownership in Germany

When looking at homeownership rates in OECD countries, Germany stands out for having a much lower rate compared to others. In fact, only 41.8% of Germans own their homes, and in some areas, this rate drops even further to just 20.1%.

One reason for this lower homeownership rate could be cultural. Germans generally have a strong aversion to taking on debt. The word for debt in German, “Schuld,” also translates to “guilt,” which suggests that borrowing money might be seen as something undesirable or morally wrong in the culture. This perception may explain why many Germans shy away from taking out mortgages, especially considering the long repayment periods, which can stretch up to 30 years.

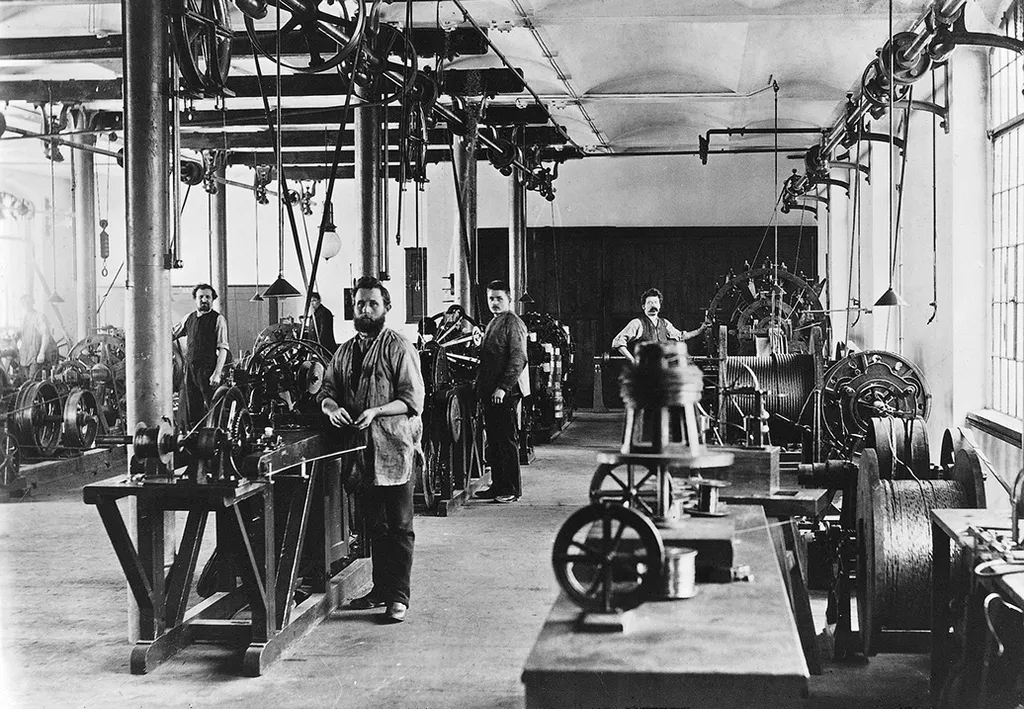

Another factor influencing lower homeownership rates, particularly in cities like Hamburg, could be the city’s historical role as a major port. In the past, sailors with disposable income often bought property because they spent so much of their time at sea. Additionally, Hamburg has a large number of wealthy residents who view homeownership as a smart investment. This leaves fewer opportunities for the average person to buy a home.

Of course, these are just theories, but the fact remains that for many Germans, owning a home is not a viable option for reducing long-term expenses. This brings me to consider alternative solutions where the government could play a role in changing the current situation and making homeownership more accessible for a larger portion of the population.

Modern Solutions to Homeownership

While homeownership rates are relatively low in Germany, there are other countries where homeownership rates are high, and some even offer near-“free” opportunities for citizens to own homes. These examples show how governments can design policies that promote homeownership and economic stability.

Singapore

Despite its small size—just 700 square kilometers—Singapore has become an economic powerhouse, largely due to its strategic government policies. With a population of 6 million, giving land directly to citizens isn’t feasible, but the government has successfully implemented policies to encourage homeownership.

The Housing Development Board (HDB) plays a central role in this success. It builds affordable homes and offers subsidies, low-interest mortgages, and financial support to cover any deficits. Additionally, Singapore’s mandatory savings system, called the Central Provident Fund (CPF), helps citizens save for home purchases. Policies like land value capture ensure that land prices remain stable, even though land is limited.

Thanks to these policies, 90% of Singaporeans own their homes today, which stands as a powerful testament to the effectiveness of these government strategies in fostering personal wealth, economic growth, and social stability.

Italy

In several small towns across Italy, vacant homes are being sold for just €1 as part of an initiative designed to revitalize rural areas that have experienced population decline. This program aims to attract new homeowners, stimulate local economies, and preserve Italy’s rich cultural heritage. However, the catch is that these homes typically require substantial renovations, with costs ranging from €20,000 to €50,000. Buyers must submit renovation plans within one year of purchase and complete the renovations within three years. Additionally, there are legal fees, renovation guarantees, and other specific requirements that buyers must meet.

While Singapore and Italy offer interesting examples of increasing homeownership, their solutions are not universally applicable. Singapore’s success is partially due to its smaller population and efficient use of limited land, which makes its model less adaptable to larger countries with different demographics. Italy’s program, while innovative, may not suit individuals who are unwilling to invest in substantial renovations or prefer urban living over rural relocation. By examining these cases, we gain insight into the various ways to promote home and land ownership—and the unique challenges each solution faces.

Historical Examples of Land Distribution

The idea of giving land to citizens isn’t new. Throughout history, many have tried to implement this concept, but for various reasons, these efforts often failed. In most cases, those who attempted to give away land for free ended up facing significant challenges, with little success in addressing the underlying inequalities. These historical examples offer valuable lessons on the complexities of land redistribution and the political forces that often prevent it from succeeding.

The Roman Republic

While reading SPQR by Mary Beard, I came across a story about a politician in ancient Rome that intrigued me. In 133 BCE, Tiberius Gracchus proposed a reform to give land from the state to Roman citizens, particularly the poor and veterans. His goal was to tackle growing economic inequality and the concentration of land in the hands of wealthy elites. Gracchus believed that land redistribution could restore balance and offer opportunities to those who had been left behind by Rome’s increasing wealth disparity.

Unfortunately, his proposal was met with fierce resistance from the ruling class. Tiberius was ultimately killed in a violent altercation, beaten to death with a chair leg in the Senate. His brother, Gaius Gracchus, tried to continue his work but also met a tragic end, despite managing to distribute some land. The failure of the Gracchi brothers’ reforms marked a turning point in Roman history, signaling the beginning of the decline of the Roman Republic, as political power became increasingly consolidated among the elites.

Lincoln’s Reconstruction Plan

In another book, The Empire of Cotton by Sven Beckert, I was surprised to learn that, after the Civil War and the emancipation of enslaved people, there was no comprehensive reform to grant them true economic freedom. After years of working without ownership, what could formerly enslaved people do with their newfound freedom? Capital, specifically land, was needed to achieve economic independence. Without land, they were left with little means to sustain themselves and build wealth.

Interestingly, I later learned from the Apple TV+ series Manhunt, which focused on Abraham Lincoln’s assassination, that there was actually a plan to provide land to newly freed African Americans. In 1865, land was being distributed to some freed people as part of an initiative called “40 acres and a mule.” However, after Lincoln was assassinated, President Johnson reversed this policy and took back the land. The backlash from plantation owners, who feared losing their labor force, played a crucial role in this decision. They complained that if freed African Americans were given land, they would no longer work on the plantations.

Had Lincoln not been assassinated, it’s possible that the economic landscape for African Americans could have been very different. Unfortunately, after Johnson’s reversal, efforts to distribute land to African Americans have been limited, and those that did occur were largely ineffective. This failure to provide land or economic opportunity to former slaves has had lasting consequences, contributing to the entrenched racial and economic inequalities that persist in the United States.

The Land Distribution to Farmers in Turkey

Another example comes from my home country, Turkey. After World War II, discussions about land redistribution to farmers were actively debated within the Republican People’s Party (CHP), the only political party in power at the time. Many saw land reform as a crucial step to improve the economic conditions of rural farmers and reduce inequality. However, landowners within the CHP, who controlled large estates, strongly opposed the proposed legislation. They feared that the reform would diminish their wealth and power.

In response to the opposition from the landowning class, these influential members were expelled from the CHP and went on to form the Democrat Party (DP), a political force that aimed to block the land reform. The DP gained significant popularity and eventually won elections, forming the government. Despite the passing of the land redistribution law, it was so heavily altered by the new government that it failed to achieve its original goals. Instead of the widespread redistribution of land, the reform was diluted, and many farmers saw little benefit.

As a result, the CHP has never regained the same level of support and has never been able to govern the country on its own since then. The failure of land reform in Turkey not only impacted the rural farmers it was supposed to help but also had lasting political ramifications, shifting the balance of power in the country.

These examples—spanning from ancient Rome to the Reconstruction era in the United States, and even into modern Turkey—highlight the persistent challenges of implementing land redistribution. Despite the good intentions behind these efforts, the concentration of power among landowners, political elites, and other influential groups has often led to their failure. However, these historical attempts offer valuable lessons about the complexities of land distribution and the barriers that must be overcome for such reforms to succeed.

Given these lessons, I believe it is now time to approach the idea of giving land to citizens with a more modern perspective. This is where I propose the concept of Universal Basic Land—a solution for countries with large amounts of unused land to tackle inequality, provide economic freedom, and fulfill a basic human need.

Universal Basic Land

Universal Basic Land (UBL) is an innovative concept that extends the idea of Universal Basic Income (UBI) to land ownership. For those unfamiliar with UBI, it is the concept of providing a set amount of money to every citizen in a country, regardless of their economic status. While UBI focuses on providing individuals with a guaranteed income to support their basic needs, UBL would provide people with access to land, giving them the freedom to determine how to use it. This could include building a home, starting a farm, or running a business. The idea behind UBL is to offer individuals the flexibility to create their ideal living and working spaces, instead of assuming that everyone wants to own a home. This concept acknowledges the diverse needs and desires people have when it comes to land use.

For UBL to work effectively, land distribution must be carefully planned to avoid the creation of isolated, underserved areas. If not managed properly, people could end up owning land in rural locations with few services or opportunities, much like the situation seen in some parts of Italy, where individuals live in remote areas with little access to the amenities and infrastructure of urban centers. To prevent this, UBL land should be spread across regions that are connected and accessible. This way, people can choose land for various purposes, such as housing, commerce, or agriculture, while still benefiting from being part of a well-developed community. For instance, someone might choose a plot for residential use, while another person might opt for land to open a business. This mix of land purposes would foster vibrant communities with necessary services, such as cafes, restaurants, and stores, all while local farming ensures a sustainable food supply.

In addition to well-planned land distribution, UBL also requires a strong transportation infrastructure. The success of UBL hinges on ensuring that new towns or communities are well-connected to one another and to larger cities. People should be able to travel easily between towns, whether for work, education, or leisure, without being dependent on owning a car. Accessible public transportation would make living in a UBL community both practical and sustainable, reducing the financial burden of car ownership and encouraging mobility.

Another key element of UBL is the ability for people to trade their land if their needs or preferences change. For example, someone who initially chose land for farming may later decide that they want to build a home as their family grows. A flexible marketplace for land transactions would allow people to buy, sell, or swap land. However, it’s important that each person can only own one piece of UBL land to prevent individuals or corporations from hoarding land. This ensures that UBL remains a tool for equitable land distribution and helps maintain a more balanced, fair system.

Of course, a potential concern with UBL is the capital required to develop the land. Whether it’s for building a house, establishing a farm, or starting a business, significant investment is often needed. To address this, financial tools such as loans or credit could play a vital role. After acquiring the land, individuals could use it as collateral to secure funding for development. Alternatively, they could choose to lease their land to others, generating income while retaining ownership. While this financial aspect of UBL would require careful consideration, it presents a valuable solution to ensure that landowners can access the resources they need to make the most of their land.

In conclusion, Universal Basic Land could offer a transformative approach to land ownership and use, empowering individuals with more freedom and opportunities. With careful planning and the right financial tools, UBL has the potential to create thriving, interconnected communities where people can shape their futures based on their unique needs and aspirations.

Universal Basic Income vs. Universal Basic Land

When the topic of income inequality, social unrest, and the rise in productivity is brought up, Universal Basic Income is often suggested as a potential solution. Proponents argue that UBI could alleviate various societal issues by providing people with a financial safety net, allowing them to live more comfortably and focus less on basic survival.

However, one of the most common concerns about UBI is the risk of inflation. If everyone suddenly has access to more money, the prices of goods and services, including rent, could rise, potentially nullifying the benefits of receiving a basic income. I share this concern, but what worries me more is that UBI might not truly address income inequality. A large portion of the money people receive would likely end up going to landlords and financial institutions, as individuals use their UBI to pay rent or mortgages. In essence, this would funnel wealth into the hands of the already wealthy, leaving the core issue of economic disparity unresolved.

In contrast, Universal Basic Land could offer a more impactful solution. If people were given access to land, the dynamics would shift. Instead of paying rent or a mortgage, individuals could use the land to build a house or start a business, gradually increasing their wealth. Over time, the land could appreciate in value, allowing individuals to build equity. Additionally, by investing in the land and developing it, people could generate income from their efforts. The government would still collect taxes on spending, but rather than going directly to landlords or banks, the money would circulate within local communities, supporting broader economic growth and helping to address wealth inequality more effectively.

Another concern often raised with UBI is the potential for people to stop working altogether. While the goal of UBI is to provide financial freedom, there’s a fear that it might discourage people from pursuing work, especially for jobs that are essential but not particularly desirable. Universal Basic Land, on the other hand, would still require people to work, though perhaps on their own terms. While they might not have to work as much as they do now, they would still need to invest effort into developing their land, whether it’s constructing a home, cultivating crops, or starting a small business. Even if they build a home, there would still be ongoing expenses—like food, utilities, and personal interests—that would require some form of income.

For these reasons, I believe Universal Basic Land is a more sustainable and equitable solution than Universal Basic Income. By providing people with land, we empower them to create wealth and stability on their own terms, while reducing the concentration of wealth in the hands of landlords and banks. It encourages personal responsibility and development, all while addressing some of the systemic issues tied to income inequality.

Where to begin?

If you’ve ever taken a look at a map of Germany with statistical data, you might have noticed the ongoing divide between East and West Germany. Even after decades of reunification, there are still significant disparities in economic indicators like homeownership rates, unemployment, and overall prosperity. The eastern part of the country tends to fare worse in these areas, with economic challenges more pronounced. This is why I believe that East Germany could be the perfect place to test the concept of Universal Basic Land.

East Germany offers several advantages for this kind of initiative. First, there is a substantial amount of unused land, especially in rural areas where the population density is lower. Much of this land remains underdeveloped, offering an opportunity to revitalize these regions by giving people the tools to create their own futures. By offering free land to people living in East Germany, the government could empower individuals to build homes, start businesses, or develop agricultural projects. These activities would not only help reduce unemployment but could also lead to a thriving local economy.

By testing Universal Basic Land in East Germany, we could see firsthand how giving individuals ownership of land leads to greater prosperity. Over time, this initiative could serve as a model for other regions or countries facing similar challenges, showing that land ownership—not just income—can be a key factor in improving economic well-being and reducing inequality.